08 Aug Abashiri, Shiretoko, Tokyo Bay, Hiroshima, and Ishigaki, Japan

Mitsutaku Makino, Fisheries Research Agency of Japan; mmakino@affrc.go.jp

Key Messages

- Japan’s diverse climate produces a wide range of marine ecosystem types.

- Increasing urbanization throughout Japan has resulted in widespread conservation efforts of resources to protect lifestyle and traditional culture.

- Differences of the local culture dynamics can be linked to coastal ecosystem changes.

Community Introduction

Japan is an island country comprised of 4 large islands and thousands of smaller islands which stretch from Russia to the north and Taiwan and the Philippines to the South. Located at the middle latitudes in the northwestern Pacific, Japan is bordered by the Pacific Ocean to the east and the Sea of Japan to the west. Due to the ocean currents and climate conditions, Japan has wide-ranging marine ecosystems from sub-arctic to tropical (Figure 1).

Figure 1: study sites

With a population of approximately 127 million(1), land and resources are of high value and protecting these areas are of high priority. Although known for its urban development, Japan is home to many coastal, rural communities which rely on primary resource production for their livelihoods.

Conservation and Livelihood Challenges

Abashiri coast is sub-arctic, salt-water lake on the northern coast of the northern island of Hokkaido. Distant from big cities, it has a small population and relies heavily on large fisheries production. Due to the amount of fishing that takes place, sea grass and sand beach conservation is a top priority for the Abashiri community (Figure 2).

Figure 2: sea grass bed in Abashiri community

Tokyo-bay is a temperate, enclosed bay located in Tokyo, on the largest island of Honshu. This area is highly industrialized with a huge nearby population. Especially over the last 60 years, urban development has increased as new residents move into the area, putting further strain on the already at-risk resources. As a result, locals have taken action in order to protect and restore the sea grass beds and their traditional seafood culture (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Tokyo Bay

Hiroshima suburb is a temperate, inland sea located in the Hiroshima prefecture on the western side of the largest island, Honshu. Distant from big cities and with a decreasing population, sea grass bed conservation (Figure 4) is very important to the traditional sea grass culture that is vanishing in the region.

Figure 4: Hiroshima Suburb

Ishigaki Island is a tropical lagoon. It is a remote island southwest of the 4 main island located close to Taiwan. Coral reefs and sea grasses are at risk due to an increasing population and a fast growing tourism industry (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Ishikagi coral reef

Shiretoko is a sub-arctic ecosystem located in the most northeastern part of the northern island of Hokkaido. Recently gaining status as a World Heritage Site, locals are concerned with how the management and conservation of this site impacts their traditional fishing lifestyle (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Shiretoko fishing community

Community Initiative

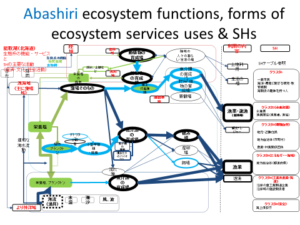

The coastal ecosystem conservation activities conducted by the local communities are part of a comparative analysis study that explores and discusses the differences of the SES conditions that each community experiences, and their influence to the nature of community conservation. The comparative study seeks to:

1) Develop integrated diagrams of coastal ecosystem functions, services, uses, and stakeholders, by collaboration with local officers and local ecosystem researchers in the different sites (Figure 7).

2) Conduct stakeholder interviews asking their interests, activities, concerns, conflicts, etc., and develop Stakeholder Tables. Also, important statistics relating to the above stakeholders are collected.

Figure 7: summary of the ecosystem functions, ecosystem service uses and stakeholders (case of Abashiri)

3) Based on above, conduct a comparative analysis among the sites, with special emphasis on the governance, meanings and motivations in each site.

Practical Outcomes

Meanings and motivations for conservation are dependent on the local culture for the ecosystem service uses. In other words, the meanings and motivations are reflecting the local way of living in harmony with t he coastal ecosystems.

- In Abashiri, local people have a strong fisheries-oriented culture, and the culture is still at the very core of the local motivations and meanings for conservation.

- In Hiroshima, seagrass is deeply linked to the local traditional lifestyle, but the community itself is diminishing now.

- In Ishigaki, the traditional coral reef culture is surviving, but the population and the tourism industry is growing very fast.

- In Tokyo, the traditional lifestyle was almost totally destroyed, but local people (mainly the new residents) are very proud of the local seafood culture.

- In Shiretoko, engaging in consistent interactions and incorporating local-ecological knowledge provided some successes between management authorities and local communities.

We found that such differences in local culture dynamics can be linked to coastal ecosystem changes. In Tokyo bay, the coastal ecosystem was almost totally destroyed, and the objective of the conservation was the revival of traditional lifestyle and culture. In Abashiri, on the opposite case, the coastal ecosystem has remained relatively unchanged, and their only objective/motivation is resource sustainability and productivity.

The comparative analyses shows that with higher biodiversity, we will have more diverse use-types and stakeholders, more conflicts, so more public initiatives are important for community conservation activities. Also, the dynamics of ecosystem and cultural changes are synchronized, and the meanings/motivations for local conservation activities are linked to those dynamics.

These relationships among the social system conditions, ecological system conditions, and the nature of the community conservation activities, should be properly incorporated when designing the conservation activities in specific areas. There is no one-fit-all approach when it comes to conservation

References

1. World Bank. 2013. Japan. From http://databank.worldbank.org/data/reports.aspx?source=2&country=JPN&series=&period

Acknowledgements

This research is being carried out with the aid of a Doctoral Research Award from the Canadian International Development Research Centre, a doctoral award from the Social Science and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) of Canada, a SSHRC grant held by Dr. Derek Armitage as part of a Coastal-Marine Transformation Project, and support from the SSHRC-funded Community Conservation Research Network (CCRN).

See below for the Japanese language abstract for this community story, “網走、知床、東京湾、広島、石垣、日本:沿岸生態系の保全を実践ファイブコミュニティ.”