03 May Eastern Shore, Nova Scotia, Canada

Tiffanie Rainville, Sadie Beaton, Jennifer Graham, Maggy Burns

Ecology Action Centre; Sadie.beaton@gmail.com

Key Messages

- A close relationship with the land is a key aspect of local identities along the Eastern Shore of Nova Scotia.

- Local community groups have been key actors in the Eastern Shore’s forestry and wilderness conversation

- These same actors are also looking to innovative combinations of new and old technologies for new ways to protect the Eastern Shore identity, including eco-tourism and adventure tourism.

Community Introduction

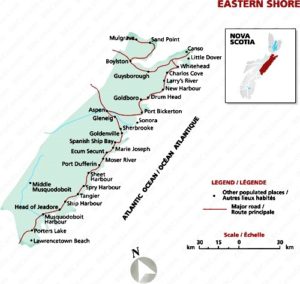

Within the eastern Canadian province of Nova Scotia, the Eastern Shore is a largely rural region of the mainland, northeast of Halifax along the Atlantic Ocean coast (Figure 1 – Map). Human habitation of the region goes back several thousand years. Mi’kmaq peoples traditionally thrived throughout Mi’kma’ki, a territory encompassing Canada’s Maritime Provinces and Gaspé Peninsula of Quebec. The Mi’kmaq traditionally hunted, fished, and camped in the region. Before European contact, Mi’kmaq populations were distributed throughout the Eastern Shore region, with concentrations nearby present day Musquodoboit, Ship Harbour and Sheet Harbour. Although Mi’kmaq retained their traditional land use patterns in these early years of contact, significant changes occurred with the arrival of English and German Protestants, who were granted tracts of land by their colonizing nations. As a result, Mi’kmaq populations were largely displaced,

Figure 1: Eastern Shore, NS. Credit: BBCanada.com

By the early 1900s, a number of fish plants, shipyards, lumber mills and gold mines helped usher this sparsely settled region into the industrial revolution. Industrialization intensified a boom-and-bust economy, temporarily increasing the population base – until many of these operations closed down in the 1990s with the impactful historical collapse of the groundfish fisheries3.

As the local forestry industry began to be increasingly managed for pulp, due to a global appetite for paper made from wood pulp, forest management practices shifted towards clearcutting. In 1977, the provincial government opted for a forestry policy aiming to double harvesting volume and, by the 1980s, clearcutting was the overwhelming norm. Increasingly mechanized harvesting technologies further accelerated the degradation of the Eastern Shore forest. These shifts in technology, markets, and policy not only degraded the forests, but also led to loss of community access to the land, and phased out most forest management roles from the community. However, recent international drivers, stemming from the United Nations’ Brundtland Report (1987) and Rio Declaration (1992) drove federal and provincial wilderness protection commitments starting in the 1990s. The Eastern Shore is home to the Acadian forest (Figure 2), a unique woodland that extends across eastern Canadian and the northeastern United States. This resilient forest ecosystem, listed as endangered by the World Wildlife Fund, is comprised of a mixture of uneven-aged hardwood and softwood trees.

Figure 2: Acadian Forest. Credit: Jamie Simpson

Eastern Shore forests have value to both local residents and the wider population as plant and animal habitat, carbon storage, storm protection, and soil preservation, along with recreational opportunities (hunting and fishing, canoeing, and camping) and other trail system activities. Access to this wilderness is valuable for economic, recreational, aesthetic and spiritual reasons. Some areas, notably the archipelago of small islands that dot the coastline, have both wilderness protection and ecotourism potential. Nova Scotia forests and their services in climate regulation, waste treatment, recreation and cultural benefits, among others, have been estimated to contribute up to $1.68 billion (1997$) annually1 and help reduce climate change damage, through storing 107 million tonnes of carbon2.

The largely rural population of 15,720 (2011) continue to pursue mixed livelihoods, with an economy based primarily on fishing, forestry, but also including some hunting (and guiding), and salmon angling. A close relationship with the land is a key aspect of local identities along the Eastern Shore and land access is critical to this deep connection, and highly valued.

Conservation and Livelihood Challenges

In Nova Scotia, the province’s Department of Natural Resources (DNR) manages most of the publicly owned forest and wilderness resources. DNR has broad responsibilities related to the development, management, conservation and protection of forests, minerals, parks and wildlife resources. Despite this, environmental and community groups believe that DNR’s relationships with forest extraction companies has dominated DNR’s motivations, often leading to management choices that diminish Nova Scotia’s natural wealth.

Much of the Acadian forest along the Eastern Shore has been logged extensively, and even-aged forest monoculture stands (same aged trees with little to no mixture of younger and older trees) have diminished its resiliency. This has impacted the Eastern Shore, as did the stunning collapse of groundfish stocks in the early 1990s, which not only resulted in significant ecological loss, but also decreased economic resiliency, driving rural depopulation. Many have speculated that there was an accompanying collapse in the sense of rural coastal identity.

The aging population of the Eastern Shore is an equally important point. In recent decades, the number of school-aged children has reduced dramatically, as many of the 30 and 40 year olds have left the region for work elsewhere. This has important implications for the Eastern Shore’s economy, which hasn’t been robust in decades.

Livelihood pressures and waves of outmigration have fragmented the population structure and identity of the Eastern Shore. Populations closer to the city are growing, shifting community identity, including the meaning of “rural”. Once defined by direct natural resource use, these towns are becoming “bedroom” communities of Halifax. A reverse influx of “new” community members, who have settled in the region over the past few decades, have also helped spur collective action around protecting watersheds, wildlife habitat and preserving Acadian forests. However, overlapping priorities have conflicted with the stewardship and access issues of the more long-time residents.

Community Initiative

The socio-ecological system of the Eastern Shore is extremely rich, encompassing a variety of relevant stories and lessons. The research in this region focuses on community conservation actions related to forestry and wilderness conservation between 1975 and 2015. The story illustrates how the efforts of key local champions helped drive an evolution of community identity over time, allowing for increased collective action related to protection both of wilderness and local livelihoods.

Various community groups have been key local actors in the Eastern Shore forestry and wilderness conversation. These groups include: The Association for the Preservation of the Eastern Shore (APES); The Eastern Shore Forest Watch Association (ESFWA); Otter Ponds Demonstration Forest; The Deanery; The Public Lands Coalition (PLC); and The Ecology Action Centre (EAC). Local actors or ‘local champions’ within the above groups were crucial drivers of change in this story, facilitating collaborations amongst diverse stakeholders to achieve transformative outcomes. Also, individuals brought together groups, which then amplified their organization, enabling them to take up greater roles as activists promoting (and accomplishing) conservation outcomes.

Background: 1970s-2000s

In 1975, Parks Canada aimed to designate a large area of the Eastern Shore as a National Park. Local communities expressed immediate concern about protecting their access to the land, preserving their way of life, and the threat of expropriation of their land. The APES formed, mobilizing collective action around the expropriation threat. After significant local pushback, the Federal government backed off. Subsequently, the provincial government has negotiated and established provincial parks and sanctuaries, especially along the coast. The National Park proposal marked the beginning of decades of changes shaped by divergent stakeholder interests around local resources, especially forests.

After the Nova Scotia government selected 31 Wilderness Areas for protection in 1990, Jim Campbell’s Barren, in Nova Scotia’s Cape Breton area, was dropped from the list of candidates in 1996. This key event led to public opposition (led by the Public Lands Coalition) and demand for the re-inclusion of Jim Campbell’s Barren. By 1998, the dropped candidate area was returned to the list, and momentum from this “win” led to a push for larger pieces of protected land at the provincial level. This fostered a sense of agency and empowerment on the Eastern Shore, even though not all residents agreed with the outcomes.

By the year 2000, a collective opinion emerged among local stakeholders across Nova Scotia, that the “industrial forestry model was not compatible with local use”. This is arguably the moment when local groups crossed a threshold into a more concerted “identity” and capacity to influence change as a coherent group.

During a subsequent Forest Forum event, participants called for a “change in vision”. This change in vision evolved into what became known as the Colin Stewart Forest Forum (CSFF), which served as a mechanism for negotiation between forestry companies and the Public Lands Coalition, without active involvement from the DNR. The CSFF quickly evolved and agreed to produce a report delineating sites for protection, with recommendations for meeting Nova Scotia’s declared goal of landmass protection, as outlined in the Environmental Goals and Sustainable Prosperity Act (2007). Submitted in 2009, the report was deemed an exceptional example of environmentalists and forestry companies coming together to achieve a common goal4.

2008 – Designation of Ship Harbour Long Lake

Ship Harbour Long Lake Wilderness Area (SHLLWA) is a 15,000-hectare wilderness between the communities of Ship Harbour and Musquodoboit harbor. Rich in ecological diversity, it encompasses more than 50 lakes, numerous streams, old forest, marshes, and waterways. In 2009, after two years of consultation and discussion, SHLLWA was officially designated under the Wilderness Areas Protection Act. This designation was one of the first positive outcomes of the collective pushes, including both regional environmental groups like EAC and local stewardship groups like the ESFWA5,6.

2009 – Caribou Mines Clear-cut

Another important threshold occurred in 2009 when a particularly visible roadside clear-cut emerged near Upper Musquodoboit (Figure 3). Local concern spread, including the formation of a ‘Save Caribou Mines’ group, and escalated when the scene was photographed and distributed by EAC and ESFW, resulting in significant public outcry around the province. The outcome was the design of a sustainable economic, social, and environmental policy. While the results of this policy remain to be seen, wide participation in the consultation process may have helped catalyze diverse groups to engage in collective action to protect a shared “sense of place”.

Figure 3: Caribou Mines Clearcut. Credit: Jamie Simpson

2009 – Otter Ponds Demonstration Forest

As part of the negotiations for SHLLWA (see above), a forest company relinquished their cutting rights on part of the public land involved in exchange for other areas nearby5. Several Mooseland community members were concerned over the company’s encroaching entitlements, fearing more clearcuts in the forests their families had used over many generations. After another highly visible clearcut appeared near the community, residents engaged in collective action.

A threshold moment occurred during a forest hike just outside Mooseland. Led by a local champion, members of various community groups began to discuss an innovative idea to help protect community and forest values in the area. These discussions led to the creation of a multi-stakeholder demonstration forest for uneven aged forestry.

By 2009, the idea had matured into a conceivable project, and was brought directly to the DNR Minister. The project aimed to create an economically viable, sustainable, and scalable initiative including community involvement, rural economic development, and uneven-aged forest management. Representatives of the four non-governmental organizations were given the opportunity to work with the lease of the public land to develop the newly formed Otter Ponds Demonstration Forest. After nearly a year of dialogue between these groups, agreements were signed on June 22, 2010.

2015 – “100 Wild Islands Legacy Campaign”

After research revealed unrecognized and globally significant never-cut boreal rainforest, Nova Scotia Nature Trust (NSNT), a land conservation organization, launched a “100 Wild Islands Legacy Campaign.” This work, driven by an environmental nongovernmental organization, happened alongside the provincial Protected Areas process, which ultimately resulted in a joint protection announcement with the province in June 2015. This included protection for an additional 1844 new hectares of land alongside the Eastern Shore Islands Wildlife Area.

The Atlantic Canada Opportunities Agency (ACOA) is helping the Eastern Shore expand its tourism potential related to these islands, as part of a broader program called the Strategic Tourism Expansion Program (STEP). The work of several local groups helped catalyze and steer this process. The funding focuses on economic development through tourism. The aim is not only to protect a “sense of place,” but also to derive economic benefit from the opportunities presented by the protection efforts of the NSNT and recent additions to provincial Protected Areas and Parks.

Practical Outcomes

Over the past forty years, much has changed along the Eastern Shore. Back in 1975, local communities were just beginning to organize against external threats to their sense of place, including wilderness protection proposals and industrial forestry. As economic and demographic changes shaped evolving livelihoods and community identity over the years, key threshold events have also helped community groups, with diverse motivations, come together to create and support various conservation actions, from a demonstration forest to protected areas to stewardship skill building projects. However, there is still a deep need to support the resilience of the Eastern Shore and its members especially through rural economic development which respects identity, ‘sense of place’, and stewardship priorities.

With a large plot of wilderness protection secured and a community demonstration forest in works, environmental groups often laud the Eastern Shore as part of a provincial conservation success story. Certainly, protection leads to measureable conservation impacts that can benefit communities, and a community demonstration forest woodlot promises to promote local ecological stewardship practices as well as aiming to achieve economic sustainability. These same actors are also looking to innovative combinations of new and old technologies for new ways to protect the Eastern Shore identity including eco-tourism and adventure tourism.

References

All information was adapted from the Ecology Action Centre’s Eastern Shore Forests: Livelihoods, “Sense of Place” and Motivation for Conservation document.

1. Costanza, R., R. d’Arge, R. de Groot, S. Farber, M. Grasso, B. Hannon, K. Limburg, S. Naeem, R.V. O’Neill, J. Paruelo, R.G. Raskin, P. Sutton, & M. van den Belt. 1997. The value of the world’s ecosystem services and natural capital. Nature, 387: 253 – 260.

2. Wilson, S., Colman, R., O’Brien, M., and L. Pannozzo. 2001. Ecological, economic and social valuation of forest resources related to resource management, harvest practices, and multiple resource usage. Genuine Progress Indicator (GPI Atlantic).

3. Charles, A.T. 1997. Fisheries Management in Atlantic Canada. Ocean and Coastal Management, 35(2-3):101-119.

4. Colin Stewart Forest Forum Steering Committee. 2009. Final Report. http://northernpulp.ca/img/pdf/CSFFreport.pdf.

5. Prest, W. 2010. Atlantic Forestry Review. Making Progress: The Otter Ponds Demonstration Forest is now a reality. Guest Editorial. 3 pp.

6. Delong, J. October 11, 2009. The voices in the wilderness. The Nova Scotian.