14 Dec Punta Allen, Mexico

Juan Carlos Seijo*, Maren Headley ; Universidad Marista de Merida (Marist University); *jseijo@marista.edu.mx

Key Messages

- Through a combination of a community-based co-management and territorial user rights approach, the Vigía Chico Cooperative has had great success in supporting resource conservation and management, and providing a stable livelihood for fishers and their community.

- Capacity for community ecosystem conservation is being strengthened by:

- Enhancing fishers understanding of the environmental and biological factors which affect the abundance, spatial availability of the spiny lobster resource and fishery profitability.

- Exchanging knowledge about the possible effects of climate change and measures that can be taken by the community for adaptation and resilience.

- Fishery harvest strategies used by small-scale fishers that help to maintain stable profits.

Community Introduction

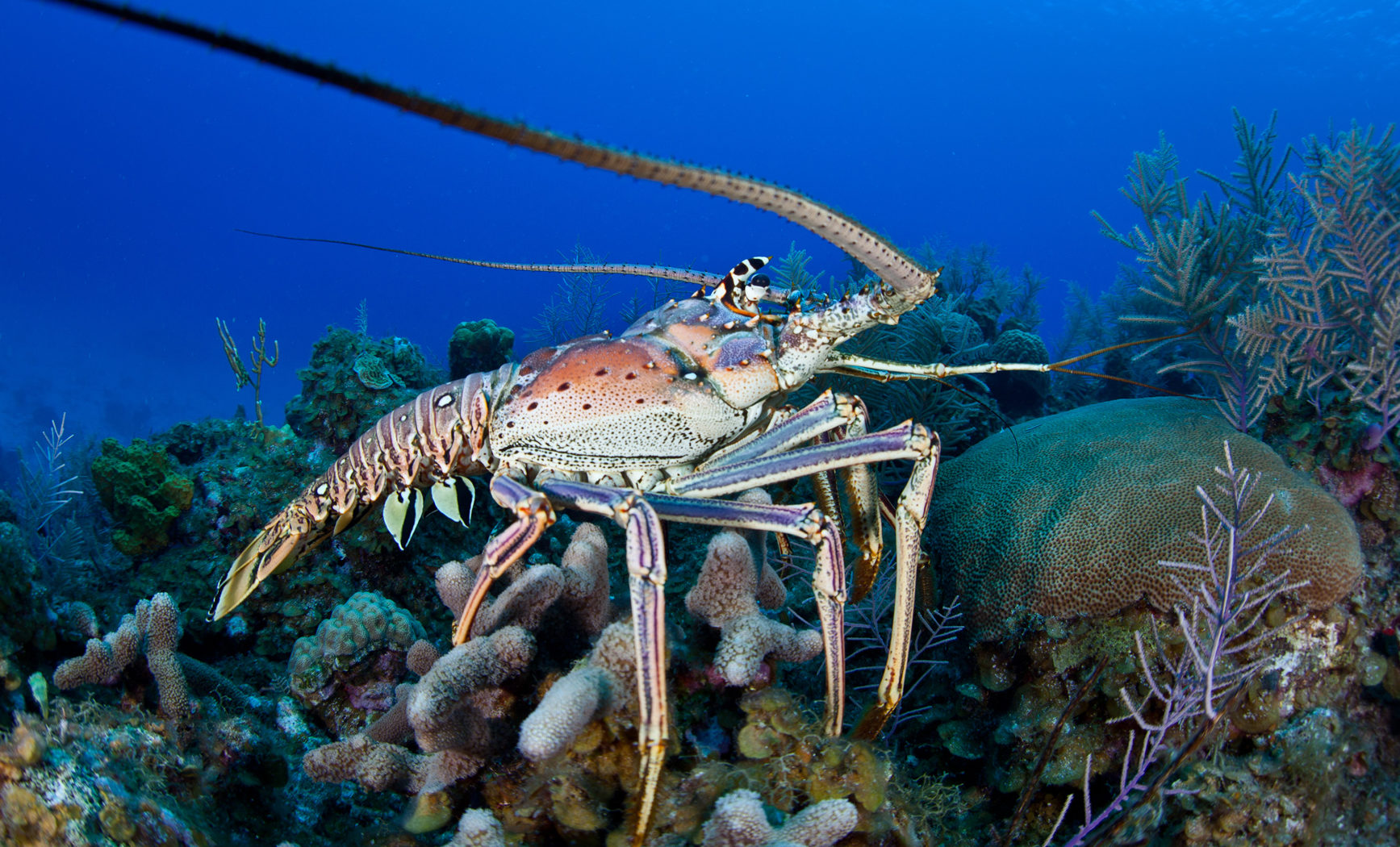

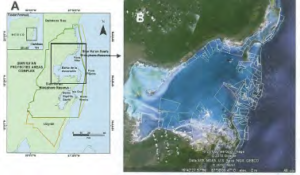

The Punta Allen community is located at the tip of a narrow peninsula, it covers approximately 1 km2 and is estimated to be less than 1 meter above sea level, with a population of around 600 persons. The major economic activities are the spiny lobster (Panulirus argus) fishery and eco-tourism. The Vigía Chico Cooperative runs this fishery, which operates in Ascensión Bay, located in the Sian Ka’an UNESCO Biosphere Reserve(1,2,3,4). The Bay covers an area of 850 km2 and includes a variety of habitats such as mangroves, corals, sponges, seagrass and macro-algae. For fishing and management purposes, the Bay has been divided up by the fishers into individual fishing grounds, locally known as “campos” (Figure 1).

Figure 1: A-Boundaries of Sian Ka’an Reserve (Source: From R. Borges, O. Guzman and K.L. Cooper in Orensanz and Seijo, 2013); B-Ascensión Bay and the individual fishing areas known as “campos” (Source: Orensanz and Seijo, 2013).

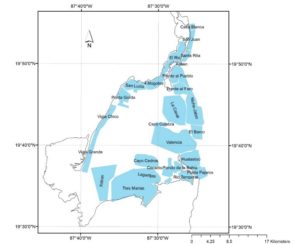

The number of individual fishing grounds identified during fisher interviews in 2014 were 115. In each “campo”, fishers deploy artificial shelters, from which spiny lobsters are harvested by free diving using a small hand held net, which allows females with eggs and undersized individuals to be replaced (Figure 2 & 3). There are 41 “campo” owners, and each owner has exclusive fishing rights within their fishing ground. These rights are supported by internal working rules of the Cooperative and are respected amongst the fishers. The individual fishing grounds where artificial shelters have been introduced are located in twenty-five (25) major fishing areas (Figure 4). These fishing areas are characterized by different habitat and bottom types, and environmental parameters e.g. salinity and temperature.

Figure 2: Handheld net used to capture spiny lobsters (Photo Credit: Maren Headley).

The fishers have many incentives for this co-management approach, including high lobster catches, high prices, and the cohesive group structure of the Cooperative. This co-management approach has helped the fishery to develop in a sustainable manner and in 2012, it received Marine Stewardship Council Certification. Most of the rules and regulations are set by the fishers themselves. Although the government has set regulations, they support the co-management approach and there is good cooperation between the government and the fishers.

Figure 3: recently constructed artificial shelters on the beach (Photo Credit: Maren Headley)

Conservation and Livelihood Challenges

Lobster stocks are a valuable resource to many fishing communities worldwide, and daily changes in catch rates and profits make it difficult for fishers to make the best decisions throughout the fishing season. Factors which can affect the abundance of the spiny lobster include habitat quality, reproduction, and environmental conditions such as marine currents, hurricanes and climate change. Adding to the complexity of the fishery, the spiny lobster has a five-stage life cycle consisting of (i) adults; (ii) eggs; (iii) larvae; (iv) post-larvae and (v) juveniles, with each stage occupying different habitats(5). Larvae develop over an estimated period of 6-8 months in the ocean, drifting with the currents and forming connections among wider Caribbean spiny lobster populations. Regions with populations which produce their own larvae (sources), and others which receive more larvae than they produce (sinks) have been identified(6). These types of populations are known as meta-populations and require resource management at the local, national and international levels. In many cases, these uncertainties lead to resource over-harvesting. It is therefore important that fishers and coastal communities have a good understanding of these factors.

Community Initiative

Being situated in a Biosphere Reserve, the Vigía Chico Cooperative has a long history of cooperating with research organizations and universities regarding conservation initiatives. In coordination with the CCRN, the Cooperative and The University of Marista-Mérida have been collaborating and conducting interviews with the fishers, collecting biological data and conducting workshops to:

• Determine fishers’ perceptions on the factors affecting the productivity and profitability of the fishery and its management implications.

• Enhance fishers’ understanding of environmental and biological factors which affect the abundance of the spiny lobster resource.

• Share knowledge about the possible effects of climate change on the community and fishery, and measures that can be undertaken taken for adaptation and resilience.

• Investigate the relationships among catches of spiny lobster, density of artificial shelters, profitability and fishing area.

Figure 4: Twenty five (25) spiny lobster fishing areas in Ascension Bay.

Having carried out fisher interviews and capacity building workshops in 2014 and 2015, the focus now is on investigating the relationship among catches of spiny lobster, density of artificial shelters, and profitability in the various fishing areas, and how fishers adapt to varying resource abundance and profitability throughout the fishing seasons.

Practical Outcomes

Seasonal and spatial differences in the catches and profitability within the fishing areas were found and were attributed to:

• The spatiotemporal distribution and abundance of the resource within the bay;

• The distance of the fishing area in relation to the port;

• The location of the fishing area in relation to the mouth of the bay;

• Artificial shelter densities;

• Heterogeneous fishing strategies where fishers adjusted fishing intensity (number of artificial shelters harvested per trip) and trip frequency according to resource abundance, to maintain stable profits throughout the season.

Lessons Learned

One of the factors that accounts for Punta Allen’s success is leadership. Transparent and strong leadership has resulted in a unified effort to conserve the spiny lobsters and ensure a sustainable fishery. The rights-based system has eliminated the race to fish since each fisher has exclusive access to lobsters in their fishing ground. This has also allowed fishers to develop a unique harvesting method very suitable to the area and the resource. There is a strong sense of community cooperation, with fishers working together for the well-being of each other, particularly in times when fishing areas are affected by heavy rainfall which results in lobster migration away from these areas. In these instances, fishers with fishing grounds in affected areas are invited to form a partnership with other fishing teams. Self-monitoring and self-policing within their community has been quite successful, given that there is an increased sense of fishing ground ownership and the influence of cultural heritage as the majority of the fishers are third generation, community founding members with strong family ties.

References

1. Miller, D.L. 1989. The evolution of Mexico’s Caribbean spiny lobster fishery. In F. Berkes, ed. Common property resources: ecology and community-based sustainable development, pp. 185-198. London, Belhaven Press.

2. Orensanz, J. M. & Seijo, J. C. 2013. Rights-based management in Latin American fisheries. FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Technical Paper, No. 582. Rome, FAO. 136 pp.

3. Seijo, J.C. 1993. Individual transferable grounds in a community managed artisanal fishery. Marine Resource Economics. 8: 78-81.

4. Sosa-Cordero, E., Liceaga-Correa, M.A., & Seijo, J.C. 2008. The Punta Allen lobster fishery: current status and recent trends. In R. Townsend, R. Shotton and H. Uchida, eds. Case studies in fisheries self-governance, pp. 149-162. FAO Fisheries Technical Paper No. 504. Rome, FAO. 451 pp.

5. Lipcius, R.N. & Eggleston, D.B. 2000. Ecology and Fishery Biology of Spiny Lobsters. p. 1-41. In: B.F. Phillips and J. Kittaka (Eds.). Spiny Lobsters. Fisheries and Culture. 2nd ed. Fishing News Book-Blackwell. Oxford, U.K. 679 pp.

6. Kough, A.S., Paris, C.B., & Butler, M.J. IV 2013. Larval Connectivity and the International Management of Fisheries. PLoS ONE 8(6): e64970. doi:10.1371/ journal.pone.0064970