17 Jul São Luis do Paraitinga and Catuçaba, Brazil

Camila Islas¹, Alice Moraes, Juliana Farinaci & Cristiana Seixas; 1camilaai@hotmail.com. The Commons Conservation and Management Group, University of Campinas (UNICAMP), Brazil

Key Messages

- Severe land degradation and environmental disasters can act as triggers to new community conservation and development initiatives and as stimulus to existing ones.

- Bridging organizations can foster community initiatives through projects addressing environmental conservation and restoration in parallel to local capacity building and community development.

- Cultural identity plays a central role in engaging communities in projects of nature conservation.

Community Introduction

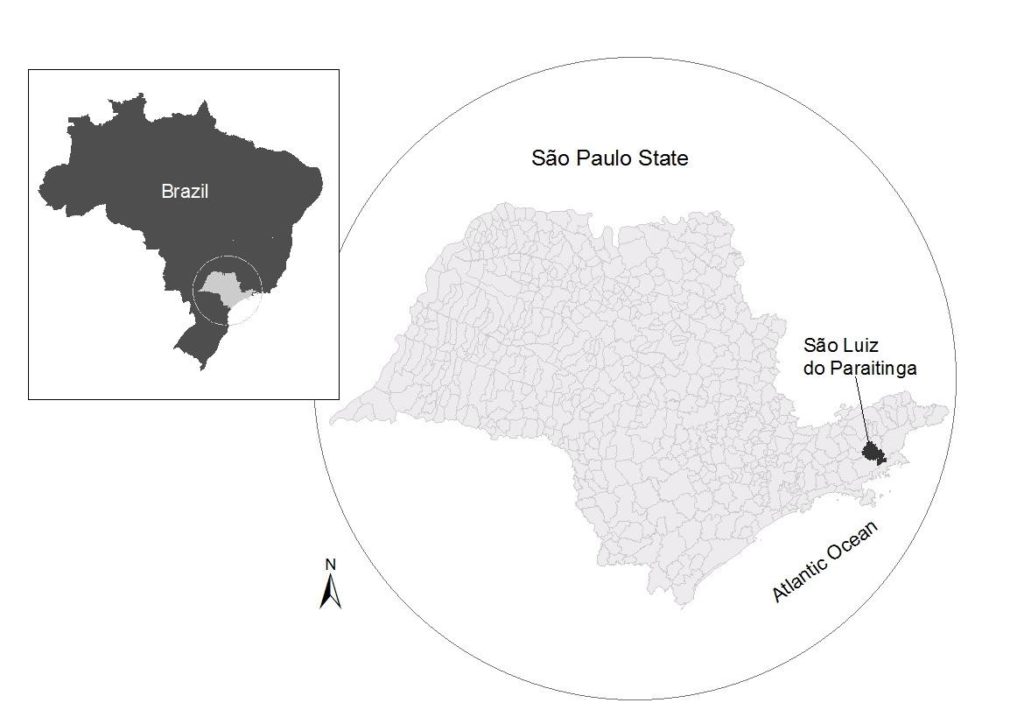

São Luis do Paraitinga (hereafter São Luis) is a municipality with about 10,000 inhabitants, located in Eastern São Paulo State of Brazil, near the Atlantic coast (Figure 1). The municipality is situated within the Paraíba Valley, which links the two largest metropolitan areas in Brazil (São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro). Out of the ~730 km2 of the municipality’s area, 10% are encompassed by a protected area (Serra do Mar State Park) and 13% are in its buffer zone. The main land uses/cover are pasture (53%) and fragmented forests (37%), while cattle breeding for dairy, forestry and agriculture are the main economic activities(1). The municipality is also embedded in the Atlantic Forest biome – a hotspot for biodiversity conservation, i.e. one of the highly threatened biomes in the world(2).

Figure 1. A) The State of São Paulo highlighted in the Brazilian map. B) São Luís do Paraitinga Municipality highlighted in the State of São Paulo map.

The landscape of São Luis has been shaped by specific material and immaterial cultural features that were strongly influenced by coffee plantations from the early 20th century and by the Caipira way of life (a local designation to a rural livelihood which involves typical food, music, tales, dances and festivities – Figure 2). The city’s architectural ensemble is the largest historical collection of the State’s architectural heritage, and its population proudly keeps alive several displays of immaterial culture(3). The local economy currently depends on public services, and the Human Development Index is among the lowest of the State’s municipalities (HDI = 0.690). In this context, cultural tourism and eco-tourism are promising alternatives for economic development.

Most rural properties (96%) in the municipality are owned by smallholders(1). Rural communities in Brazil are important social-ecological systems as they sometimes have fragments of forest, provide shelter to wild animals (serving as habitat and stepping-stones), generate various ecosystem services, and are also home to human communities and their livelihoods(4). In this context lies Catuçaba, a rural district in São Luis do Paraitinga municipality. The district comprises a small village with around 1,000 inhabitants, and its surrounding rural neighborhoods. Most inhabitants make their living from small-scale animal husbandry and other smallholding activities(4).

Figure 2: Traditional dance presentation at the central square, in front of the main church, during the festivity of the Holy Spirit in São Luis do Paraitinga, 2016.

Until a few decades ago, the village was partially isolated from the urban center due to poor access, but now, Catuçaba has improved access to infrastructure, education and health. The road leading to the village is 14 km long and was paved 15 years ago, facilitating people’s access and products transportation. Tourism-related activities are becoming more common each day due to its beautiful landscape, pleasant climate and historical farms.

Conservation and Livelihood Challenges

Land degradation is longstanding in the region. Agriculture has been practiced since the settlement of the first colonizers, in the late 17th century, in spite of the hilly landscape and soils’ low nutrient availability and permeability(1). Economic cycles (cotton, coffee, agriculture and cattle), with poor soil management techniques, contributed to land degradation, impoverishing the soil, and most recently covering the land with Brachiaria, an invasive exotic grass that feeds the cattle and worsens soil permeability. As a result, cattle productivity has declined and many landowners fell back on other activities to complete their income. Meanwhile, rural out-migration, due to the promises of better job and education opportunities in urban centers, hampered the availability of rural workers and lowered social cohesion. Currently, land degradation and such social context threaten most of the traditional livelihoods.

On January 1st, 2010, São Luis suffered from a flood of great magnitude, when the river crossing the downtown area raised over 11 meters above its regular level in a matter of hours, largely damaging the historical buildings and affecting the whole population – both urban and rural. Fortunately, there were no fatalities. Besides the high precipitation registered in the end of 2009, this flood was caused by factors linked to land degradation in rural areas, such as soil compaction in degraded and poorly managed pastures, fires commonly used to clear land, scarcity of forests near watercourses, and human occupation of floodplains.

Community Initiative

In the face of the disaster’s intensity and tremendous material losses, the population showed a remarkable capacity to self-organize in order to cope with the emergency situation and, later, to rebuild and restore the functioning of the city(5). Since the flood in São Luis, the territory as a whole has been targeted by diverse projects focusing on forest restoration, agroecological production and capacity building.

The flood of 2010 stimulated new and ongoing community initiatives, mostly with the help of local and regional NGOs and government organizations. During the post-disaster reorganization phase, the community actively participated in decisions regarding the reconstruction of historical buildings and other issues. In addition to engineering work conducted by the government initiative, most post-disaster initiatives focused on keeping the vibrancy of local cultural manifestations(5).

Figure 3: The scenic landscape around Catuçaba district: degraded pastures and patches of biodiversity-rich Atlantic forest covering its hills and valleys.

The community also showed a remarkable sense of belonging and place attachment, both in São Luis as in Catuçaba and its surrounding area (Figure 3). The tragedy seems to have reinforced this sense of place and local people’s capacities of coping and recovering their community life with their own hands, but they also acknowledge and are grateful for all the solidary help they received from external people and institutions(5).

One of these community initiatives working to improve conservation and livelihoods is the “Comunidade da Vila” (Village Community). In 2012, the Learning Community initiative began in Catuçaba. The main goal of the project was to promote an environment for reflection about nature conservation and local development, and to facilitate the planning of collective actions(6)(7). By meeting with local people, this initiative planned and organized several cultural events and community actions over three years(8). Although the project ended in 2015, the community continues to meet(3), focusing on a street market with local products, tourism-related activities and festivities.

A local NGO, Akarui, has been developing projects for nature conservation integrated with socio-economic development in the region for over nine years. After the 2010 flood, their prominence increased as Akarui members’ attachment to and knowledge about the territory, in addition to their technical expertise, have led efforts to sustainable development of rural areas of the municipality. Akarui has carried out projects regarding socio-environmental characterization, forest restoration, agroecological transition, pasture management and improvement of farmers’ income.

After the most recent extreme events (the 2010 flood and a severe drought in 2013 and 2014), more community members got interested in taking part in restoration projects, and a growing number are willing to adopt agroecological principles to their production. An Agenda 21 plan, built through participatory methods for the watershed, including guidelines for its sustainable development, is a featured product of this NGO. The institution acknowledges rural communities as their main partners(1).

Finally, another initiative named REDE SUAPA (acronym in Portuguese for The Upper Paraíba River Sustainable Development Network) began work after the 2010 flood. This network encompasses diverse stakeholders including local leaders, local and state government, local and regional NGOs and researchers, who meet voluntarily in the municipality. In addition to project development, this network creates synergies among diverse ongoing efforts and aims to influence public policies, based on a systemic view of the territory, promoting ecological restoration, sustainable farming and community-based tourism. For instance, REDE SUAPA wrote an open letter addressed to the candidates running for Mayor in 2016, asking for their commitment with priority guidelines for urban and rural sustainable development in the municipality.

Practical Outcomes

The development of initiatives is neither easy nor fast, but they have certainly been flourishing and creating arenas for community learning, empowerment, and development in São Luis do Paraitinga (including Catuçaba). Although the 2010 flood was an important trigger to various initiatives, it is still unclear how successful they will be in terms of mitigating the risk of floods in the future.

These bottom-up initiatives have valorized rural livelihoods and fostered opportunities for people to remain in rural areas. Inhabitants have been self-organizing to strengthen their cultural identity (Caipira), preserve local traditions (e.g., festivities and foods), and promote local development, with an overall understanding that their good quality of life depends on nature conservation(8). Small, low-cost initiatives triggered improvements in the community capacity to organize and act collectively for a common goal(6)(7), although a broader participation of community members in such initiatives remains a challenge.

Bridging organizations, such as NGOs and University teams, play a crucial role in linking local stakeholders with one another and with outside institutions (e.g., State Environmental authorities and funding agencies), facilitating learning opportunities, fund raising and providing access to technical advisory(8). While creating environments where diverse local and outside stakeholders can interact and collaborate (Figure 4), these initiatives have created a feedback loop, which is attracting more and more initiatives.

Figure 4: Caipira meeting in January 2017, where members of Catuçaba community and their external supporters discussed local development, nature and culture.

Currently, several stakeholders are joining efforts to work synergistically to positively transform the region’s landscape at the watershed level, for instance through REDE SUAPA. These efforts benefit from both bottom-up and top-down initiatives, taking into account both local knowledge and technical/scientific expertise, and involving stakeholders with different levels of political power. Above all, these efforts involve a diverse array of individuals who believe in a more sustainable and just society, and struggle year after year to accomplish their vision.

In face of socio-ecological change over the last decade, various community initiatives towards conservation and social development have emerged in São Luis do Paraitinga. Many tourism-related activities had already been developing, especially those regarding ecotourism (e.g., farm hotels and rafting) and cultural tourism (e.g., religious, art and local food festivities). More recently, other community initiatives were established as local markets of agroecological products and craft fairs. After the 2010 flood, the municipality drew the attention of many governmental and non-governmental organizations, favoring the emergence of new environmental and social initiatives. The success of these initiatives has depended on population engagement and participation, as well as aligning to local demands and to the inherent dynamics of the local social and ecological systems.

References

1. AKARUI, 2017. Subsídios para um plano de restauração florestal da bacia do Chapéu, São Luiz do Paraitinga, SP. São Luiz do Paraitinga, SP, 58 p.

2. Myers, N.; Mittermeier, R.A.; Mittermeier, C. G.; da Fonseca, G.A.B.; Kent, J. Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities. Nature 403, 854-858.

3. Farinaci, J. S.; Pereira, L. A. M.; Dias, A. C. E.; Moraes, A. R. & Seixas, C. S. Núcleos de aprendizado em conservação e desenvolvimento integrados: O caso da comunidade de Catuçaba. (Learning groups on integrating conservation and development: the case of Catuçaba Community) Poster presented at the I Community Outreach Meeting, State University of Campinas (17th June 2015).

4. Moraes, A.R., Farinaci, J.S., Vieira, S.A. & Seixas, C.S. 2016. Does perception on ecosystem services quality differ among stakeholders in a rural social-ecological system? A case study from Brazil. Oral presentation at the 2016 Latin America & Caribbean ESP Conference, Cali, Colombia (October 2016).

5. Farinaci, J. S.; Islas, C. A; Moraes, A. R. & Seixas, C. S. (in Prep): Cultural identity as a central asset for community resilience.

6. Seixas, C.S.; Farinaci, J. S.; Bahia, N.C.F.; de Araujo, L.G.; Prado, D.S.; Dias, A.C.E.; Abrahamsson, L.; Chamy, P. 2013. Annual Report of the outreach project “Núcleos de aprendizagem comunitária em conservação e desenvolvimento integrados” (Learning communities on integrating conservation and development) – Year I.

7. Seixas, C.S.; Farinaci, J. S.; Bahia, N.C.F.; de Araujo, L.G.; Prado, D.S.; Dias, A.C.E.; Abrahamsson, L.; Chamy, P.; Moraes, A.R.; Islas, C.A.; Ummus, R.E. 2014. Annual Report of the outreach project “Núcleos de aprendizagem comunitária em conservação e desenvolvimento integrados” – (Learning communities on integrating conservation and development) – Year II.

8. Araujo, L.G., Dias, A.C.E., Prado, D.S., De Freitas, R.R., Seixas, C.S. (orgs.). 2017. Caiçaras e caipiras: uma prosa sobre natureza, desenvolvimento e cultura. CGCommons & PREAC/UNICAMP, Campinas. Available at: <https://www.communityconservation.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/Caicaras_Caipiras_booklet_Araujo_etal_ago2016.pdf>

Acknowledgements

We thank the population of São Luis do Paraitinga and, in particular, of Catuçaba community, the NGO Akarui, and REDE SUAPA for their commitment and availability for our projects. We also thank SSHRC/CCRN, CAPES, CNPq, PREAC/UNICAMP and FAPESP for funding. The project also received a strong support from our entire CGCommons Team (The Commons Conservation and Management group at University of Campinas, Brazil).